WILD

As three of the many million Londoners who live our day to day lives in this infamously hectic city we were drawn to this idea of escaping our immediate urban landscapes, into something wild. Our fast paced surroundings ignited a longing for change that so many of our extracts possess.

Henry David Thoreau’s infamous field guide to ‘life in the woods’ Walden is pivotal to our understanding of this anthology’s theme ‘WILD’. Walden presents the wild as an essential part of life “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life” Walden promotes the idea of stripping back from excess and going into a wild physical landscape in order to find meaning.

Many of our extracts grapple with the idea of stripping back, of liberating oneself both physically and mentally in order to explore one’s essential identity. They delve further into the idea that somehow this return to wildness or nature can allow for true freedom and authenticity.

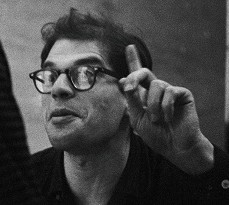

Wild as a concept is inherently subjective, what appears wild to one could be tame to another. In society and in art there are specific boundaries that separate ‘wild’ from order, nature from civilisation and freedom from captivity. Spanning over one hundred years, our extracts explore these oppositions and show their effects art. All of the artists; Ansell Addams, Henri Rousseau, Spike Jonze, Allen Ginsberg, Wendell Berry, Lou Reed and Henry David Thoreau all explore different concepts of ‘wildness’ through different media. This anthology therefore consists of film, painting, poetry, song and photography offering to you, the reader a multifaceted insight into the concept of WILDNESS.

We want to share our journey of escape, into the different kinds of wildness that our extracts took us on, and show how such a journey, of exploration and discovery can be taken by anyone. We want to illustrate that this voyage can lead to self- awareness and a liberation from the shackles of society.

Our extracts link to the concept of ‘wildness’ in contrasting ways. A central aspect of our theme is the tension between physical and psychological wilderness. The common thread between our extracts is the idea that artists, and in turn humanity are often compelled to create art that is a testimony to the beauty and mystique of that which is abnormal or unconventional.

The natural environment portrayed in Ansel Addams’s photograph, from the 1930’s and Rousseau’s The Dream both represent our most traditional representations of nature as the ‘wild’. They are both very different expressions of wildness to what we see in Lou Reed’s Walk on The Wild Side or Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ where we see wildness in terms of its mystique and abnormality.

Our cover photo is an original piece that we created, melding all of our extracts into one through the symbol of Thoreau’s cabin from Walden, we felt that it was a perfect representation of a relationship between the physical ‘wilderness’ and humanity.

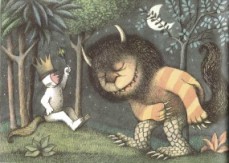

Like Rousseau (Paris) we were entrenched in an urban jungle and because of this found inspiration to present an image of a natural wilderness through the form of painting. In his 1910 painting the dream, Henri Rousseau explores the relationship between wilderness and humanity through the medium of painting. This traditional form of art is juxtaposed against the more contemporary formats, of film and pop song.

In an interview with Rolling Stone magazine prolific Italian director Federico Fellini said that ‘cinema uses the language of dreams’. Nothing seems more appropriate when looking at Spike Jonze’s oneiric adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s children’s story Where the Wild Things Are (2009). It portrays a physical dream-like journey for protagonist Max, who escapes from the shackles of his familial life and travels into an aesthetically pleasing landscape surrounded by monsters who crown him their king. The monster characters and Max himself exhibit ‘wild’ behaviour, running riot through the woods and staying up all night (the ultimate childhood fantasy).

We linked this kind of relationship between the potentially monstrous and humanity to The Dream which works similarly through its portrayal of a woman in the jungle surrounded by animals (tigers, snakes, lions etc.). Both of these works therefore show similar kinds of wildness that are grounded in a ‘real’ physical world.

Max’s childhood longing for wildness and to deviate from the norm shows that a yearning to go into/be ‘wild’ is ubiquitous in humanity, from childhood (Sendak and Jones seeing through the puerile lens of Max ) to the last days of your life (Rousseau’s painting being one of his last) this metaphysical quest remains present.

The film and Lou Reed’s 1972 hit ‘Walk on the Wild Side’ plot out physical and emotional journeys of wildness. Max and Reed’s characters, such as Little Joe and Jackie transform in terms of their locations that may or may not be based in the physical world. Max travels from the human world of his bedroom to the world where ‘Wild’ things run free whereas Reed’s Jackie travels from safe controlled society into the realm of drugs and Warhol’s infamous ‘factory’.

Max’s departure from the real world can be interpreted as merely a dream, which is one of the reasons that his journey can be considered a psychological one. This can of course be linked to Rousseau’s The Dream because of its title. The idea of wilderness being a dream is present in the portrayal of nature in Addams’s photograph of the Merced River. The photograph is dream-like, especially from a modern perspective the land seems untouched and immaculate in its raw beauty.

In modern society the term wild is also associated with noise and disruption,yet some of our extracts suggest a certain calm that can only be found in the wild. This is perfectly encapsulated by German word Waldeinsamkeit which means the feeling of being alone in the woods, and was the inspiration for Thoreau’s Walden. This links strongly to our extracts exploring the concept of solitude in the wild, and symbolises this relationship between humans and the wild.

Poetry is often seen as most true or ultimate use of language. Robert Frost said that ‘poetry is when an emotion has found its thought and the thought has found its words’. Traditional anthologies often consist of a surplus of poetry, we chose to use two very contrasting poems (in style , content and the kind of ‘wild’ they represent/explore) to exhibit how broad the representations of ‘wildness’ in art can be. Berry’s poem published first in 1985 explores a physical wildness, defined by a sense of tranquility. Conversely Ginsberg’s Howl is a visceral expression of untamed human thought. Howl is very different from the other extracts, it documents a kind of explosion of expression through Ginsberg’s quick paced almost ritualistic narrative voice intensifying its performative aspect.

The first thing that struck us when comparing the two poems was the stark contrast of the symbolism in their titles. While Berry’s title ‘The Peace of Wild Things’ evokes a peaceful image Ginsberg’s immediate curt Howl alludes to the more sinister aspect of humanity.

Since the 17th century there has been an abundance of poetry which uses nature and the wilderness as its inspiration. Romantic poetry in particular, as a reaction to the industrial revolution was infatuated with the natural world and idea of the sublime, being an awe inspiring notion. This transcendent experience, is portrayed on different levels in the poems. Berry captures the serenity associated with the sublime and Ginsberg conversely the mystique and darkness that it holds.

Keeping in mind the intrinsically patriarchal nature of the western canon, we realised that all of the artists we chose were male and ‘western’ in origins, which could suggest that this is considered a characteristically male quest in life and art. This gave us the opportunity to understand the specifically male vision of wildness, but in a new way in pieces of art that are not focused solely on woman as the primary opposition to order. Our extracts explore both the male position as distanced from the wild, so the voyeur such as Addams’ photograph as well as being a part of the wild landscape like in Reed’s song.

We wanted to further situate this exploration of perspective and showcase, our accompanying moodboard features an array of artists exploring and expressing different kinds of wildness. Which shows that ultimately it is a purely human quest.

Seminal abstract artist Wassily Kandinsky in Cologne Lecture, a piece about his personal artistic evolution maps out two impulses that were pivotal to his painting process ‘1. Love of Nature, 2. Indefinite stirrings of the urge to create’. Many of our extracts interlink these two realms inspirations. This interaction between the wild and a necessity to create plays out in our extracts. This compulsive side to creativity hints at the fact that art (and the concept of wild) often evokes visceral emotional reactions. Fear, of the ‘other’ is a very common response to art, and religion is often used as a coping mechanism to deflect this anxiety.

Spirituality and religion are recurring themes in our extracts. Religion is considered a component of civilised society that adheres to certain moral and social codes, which diverting from is automatically ‘wild’. Within the literary canon the church generally presents itself as the opposite to wildness, and in many of our extracts this position is connected to the Garden of Eden. This link to the fall of eve and in turn humanity represents how religion is seen as a way of keeping this inherent wildness at bay.

Rousseau’s painting can be seen as a direct presentation of the Garden of Eden, suggesting a deep desire to return to this place of innocence, where society was non-existent and the wild seemed to be a boundless environment. Addams’s work also has religious connotations, it appears heavenly and angelic. The Merced River photograph appears untouched. Berry’s poem suggests that the relief from chaos which the natural world offers him is spiritual. Berry is an environmentalist, whose politics are aligned with the questions that Addams’s photo evokes, such as the reminder that humans can have such a deep impact on nature. Ginsberg on the other hand presents religion negatively, suggesting through his symbol of Moloch that it is monstrous and oppressive.

Walk on the Wild Side has somewhat ironic religious connotations. It’s heavily hymnal form is a criticism of western religious tradition. It ironically becomes a kind of religious anthem for the Church of Rock and Roll and Andy Warhol. In this sense Reed is the serpent tempting the listener to go into the ‘wild’ and to allow themselves to be corrupted. The journeys taken by Reed’s characters away from the norm, into the territory of wildness can be seen as spiritual in their essence. They are tempted into darkness, crossing the thresholds of societal and religious conventions and into wildness.

Escapism in our extracts facilitates an environment where personal and collective experiences of the tension between order and chaos, captivity and freedom and the intensity of the human experience in relation to nature are explored. From the child escaping parental authority to the poet seeking solace in the woods each of our extracts deal with escapism in different ways.

For both the narrator in Berry’s poem, Lou Reed and Max the protagonist in Where the Wild Things Are their escape is portrayed as a journey from the safe space of home, or their comfort zone into a new community or environment that can be seen as ‘wild’. This perpetuates the idea that the ‘wildness’ of an action may lie in the fact that society may not accept that choice or decision, but that this decision may lead to true self-knowledge and happiness, suggesting that it is ‘walking on the wild side’, despite its perhaps scandalous connotations that can lead to truth.

Ginsberg with Howl contrastingly creates an image of a chaotic raw space in society which is to be escaped from. The reader is transported once again, but this time into a a harsh reality of suffering and exploitation. The contrast between these two extracts highlights the subjectivity of ‘wildness’ and ‘home’ further suggesting that there can never be one true interpretation of the concept. Wild is personal, wild is whatever you deem it to be. Wild is alluring.

To conclude, the concept of ‘Wildness’ is eternally interesting because of its inherent subjectivity. Wildness evolves with society, and can be seen as a reflection of its time. The meteoric rise of social media has meant a deep shift in societal perspectives of wildness. Like our fast paced society the definitions of chaos and order are constantly changing so we look forward to finding out what the next cultural forays into ‘wildness’ will be.

Perhaps the most radical ‘wild’ art can only inversely be to return to the more physical modes of representing experience, so in the face of a predominantly ‘digital’ world the most radical deviation and escape into the wild is to return to the ‘real’ world in our relationships to nature, art and ourselves?

We have only offered you six pieces, but we hope that these ignite a desire for wildness in yourself. We hope that this anthology inspires you to delve further into art that is ‘wild’ exploring and learning about what your own personal, subjective definition of the concept is. What will be wild next?

Escape into our anthology, into whatever you deem as wild through our journey of exploration in art that we and many before us saw as ‘WILD’.