Imprisonment

The Transcendence of Imprisonment

Although we would find it extraordinarily hilarious to delve into the quirks of prison life, this anthology, unfortunately, is not a substitute for the Surviving Imprisonment for Dummies guide. So, expect no mention of: how to make shanks; how to rock that grey, white, or orange jumpsuit; how to stomach the food; how to get through your first fight; or how to evade all unwanted sexual advances. This anthology will be quite depressing, but then again, how can you see the glass half-full when you know your cellmate just gulped the lot? We will, however, explore the unacknowledged instances of imprisonment by presenting a case of demonic possession and the incarceration of a cannibal to you, our honourable jury.

We aim to transcend the definition of imprisonment by exploring the facets of this solely human construct. This anthology reflects upon whether ‘the situation outside of you […] control[s] your behaviour or [if] the things inside of you, your attitude, your values, your morality allow you to rise above a negative environment’[1]. We have achieved this by selecting a spectrum of extracts to illustrate the daily and extreme forms of imprisonment. For any of you who hate to analyse anything, please see this as your get-out-of-jail-free card moment; we will do all of the work for you!

So let’s begin our stint in jail. Many are confined by their definition of ‘imprisonment’, as most will discern it as being incarcerated. However, we believe this interpretation barely scratches the surface, and through this anthology we aim to expand your minds to a world of alternatives. We interpret imprisonment as an absence of a freedom, which can be manifested through loss of control, thought, movement, or even the senses. Most importantly, this doesn’t just exist in a cell behind bars with a dingy metal toilet for a bedside table. In the real world, imprisonment translates to relationships, societal expectations, mentality, currency, and religion, to name a few. It follows you as you go about your day, creeps into your mind without a peep, we are all prisoners in some way. Conversely, in the fictional world, this can manifest as being imprisoned as a result of your deathly touch, because you eat people, or because your mind has been invaded by an otherworldly entity…

You’re probably wondering why you should read what seems like quite a gloomy collection of extracts. Well, imprisonment has become more relevant to mainstream media through widespread fascinations with prison life. In recent years, prison documentaries and fictional shows based on life behind bars have surged in popularity as demonstrated by: Making a Murderer, 60 Days in Jail, Orange is the New Black, and American Crime Story: The People v OJ Simpson…, with special thanks to Netflix. So, we are jumping onto the train of prison resurgence, yet planning a ‘prison break’ by delving into unconventional states of powerlessness and exile.

Why don’t you release yourself from social media and the grindstone of working life, and wander through the mind of someone who has been invaded by a demonic entity for a moment or two? It can’t do much harm…or could it? After all, ‘few people are completely unchanged or unscathed by the experience. At the very least, prison is painful, and incarcerated persons often suffer long-term consequences from having been subjected to pain, deprivation, and extremely atypical patterns and norms of living and interacting with others’[2]. So, due to this propensity of change that prisoners experience, don’t be alarmed if you also notice an alteration in your perceptions through reading this anthology; it is intended.

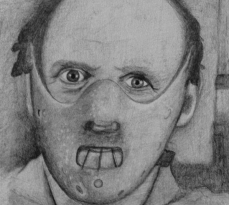

The extracts you will find below discuss the two most distinct forms of imprisonment: mental and physical, along with more abstract and specific forms. Although each extract is based between the 20th and 21st Century (written predominantly by women), they are vastly different from one another and provide a broad platform to explore less recognised forms of imprisonment. Additionally, we found it interesting and important to share the work of women who are tackling a subject that is heavily associated with the male gender, especially as women ourselves. Sub-themes and imagery have emerged which consequently link particular texts, including: torture, claustrophobia, being trapped by a memory, the collar and self imprisonment. We have ensured there is a quintessential, yet tantalisingly sincere prison excerpt in the form of The Silence of the Lambs, as well as portrayals of marital imprisonment embodied in a ruby choker in The Bloody Chamber. Let’s introduce our extracts alongside our suggested reading route (Cat videos at the ready?):

1. The Silence of the Lambs

“He feeds on pain, and that’s his game. Somebody who loves pain, but is behind bars and is not able to inflict it, and will get it anywhere he can.”[3]

We recommend watching this excerpt first because it depicts incarceration, the most obvious form of imprisonment; a state of confinement behind bars. A significant factor that contributed to the inclusion of this clip, is the way that the film shows the perspective of the prisoner from an outsider’s point of view. The clip introduces us to the cannibal serial killer, Dr. Hannibal Lecter. The way that Dr. Lecter is presented to us implies that he is to be condemned; and when you eat your victims, this is perfectly justified.

2. Shatter Me

‘1 window. 4 walls. 144 square feet of space. 26 letters in an alphabet I haven’t spoken in 264 days of isolation.’

Similarly to The Silence of the Lambs , Tahereh Mafi’s Young Adult novel concentrates on the physical imprisonment of Juliette, the protagonist, within an asylum due to her lethal touch. “[S]he [is] locked in a dark corner and afraid to speak,”[4] and throughout this extract this shines through. However, in contrast to the film, this text presents imprisonment from the imprisoned perspective. The use of the first person narration allows readers to fully enter the mind of a prisoner, demonstrating not only what it feels like to be imprisoned but also the physical and mental effects that imprisonment has.

3. ‘The Monologue’

“I left nothing to chance; and chance at its cruellest reached out and hit me.”

Following on from Shatter Me, ‘The Monologue’ incorporates mental instability into the succession of extracts. We can all relate to this snippet, which portrays a frustrating protagonist who is shackled by the weight of her past and fails to recognise a way out. The oppression of women in Paris heightens this situation, as she finds no comfort in her daily life to deal with the death of her daughter or failure of her previous marriages. She exhibits typical signs of the French phenomenon, mauvaise foi, coined by De Beauvoir herself and our good old pal, Jean-Paul Sartre. If there is a way to blame another rather than identify her own mistakes, she will utilise it.

4. ‘The Bloody Chamber’

“…his wedding gift, clasped round my throat. A choker of rubies, two inches wide, like an extraordinarily precious slit throat.”

In a similar manner, the relationship between these newly-weds depicts the ultimate social form of imprisonment. In contrast with the protagonist’s rebellion against social expectation as seen in ‘The Monologue’, the heroine of Carter’s short story submits to patriarchal and female expectation. As the eponymous and titular short story of the collection, The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories is fraught with images of the oppressed female and social imprisonment. Exhibiting unsurprising feminist slants, Angela Carter presents a story of marital brutality, whereby the protagonist must allow herself to embody the attentive, submissive wife role for fear of being murdered. Alongside this depiction of happily married life, the inclusion of the ruby choker provides insight into Carter’s deepest critiques of patriarchy and female complicity.

5. The Bell Jar

“…wherever I sat — on the deck of a ship or at a street café in Paris or Bangkok — I would be sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air.”

As evident in Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar, the prevailing mood in the late 19th and 20th century was that mentally ill individuals should be institutionalised. The extract depicts the physical imprisonment endured by the clinically depressed protagonist as she is restrained in order to prevent her from committing suicide. Institutions are seen as places for treatment and provide a sense of security for both the mentally ill and society. However, through the allusion of the bell jar, these institutions are also depicted as places of segregation and seclusion, where people are ‘being forced to adapt to an often harsh and rigid institutional routine, deprived of privacy and liberty, and subjected to a diminished, stigmatised status […] [which] is stressful, unpleasant, and difficult’[2]. The chosen passage therefore stresses the need to acknowledge the constraints felt by those who are exiled from society as a result of a mental illness. The Bell Jar presents the role of relationships in imprisonment, which is also seen in ’The Bloody Chamber’ and ‘The Monologue’.

6. Queen of Shadows

“…he had struggled in those final seconds before the collar of black stone had clamped around his neck”

Finally, we suggest you read this extract last, as it is the furthest from reality. Sarah J Maas brings to life Dorian, a young prince trapped in his own mind. Similar to The Bell Jar , Dorian experiences mental manifestations of imprisonment through an ‘experience of being out of control’[1]. Prince Dorian is perhaps, out of all the characters whose situations we explore in this anthology, the one who has “one of the worst fates that someone can deal with”[5]. An otherworldly entity called a Valg Prince is able to invade his mind due to a collar placed around Dorian’s neck. The ruby choker in ‘The Bloody Chamber’ mirrors this collar, which allows the protagonist to be overpowered and controlled like a marionette. Through third person limited narration, readers are able to visualise the fantastical situation of being mentally and demonically imprisoned and read the repercussions this has.

Texts that did not survive the first night in jail:

The removal of ‘Labyrinth’, W.H. Auden

This poem was initially considered as it would portray imprisonment through a different medium. The poem considers the physical trappings of a labyrinth, as well as the existential imprisonment of life and its indeterminacy. We, however, have replaced this option with Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar as this presents the mentality of a depressive making the text more relatable through its portrayal of everyday occurrences.

And also: This Earth of Mankind, Pramoedya Ananta Toer

Toer was a political prisoner under the Dutch colonial rule in Java, and whilst imprisoned, he managed to smuggle the entire manuscript of this book out into the world. Reasons for cutting this from our final anthology simply lie with the necessity to take advantage of our online platform and include a form of digital media. Therefore, we replaced this text with The Silence of the Lambs as it covered the literal end of the imprisonment spectrum.

Other routes that we could have pursued for the theme of imprisonment include slavery and the colonial. We recognise that there are also many other viable readings that fit perfectly into our collection, but our current selection embodies our aims and guides the transcendence of imprisonment. You are jailed in a stereotypical prison setting in the thriller, The Silence of the Lambs and are guided through the gradient from the dystopian in Shatter Me and the fantastical in Queen of Shadows. Just like a prison jumpsuit, you could say this selection constitutes a one-size-fits-all anthology, at least genre-wise.

So, you be the judge on whether our prisoners are headed for the gallows or are just destined to an existential pit in which they can wallow in self-pity.